Who Should Be Allowed to Speak at Berkeley Carroll?

Black Lives Matter is an “anti-American radical movement.”

The BLM movement has “a visceral disdain of America’s pluralist society.”

Members of the movement paint a “near-pathological picture of black victimhood.”

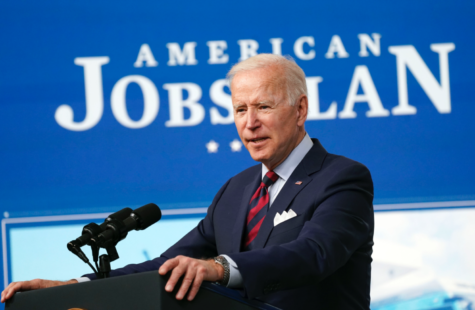

Should students at Berkeley Carroll be exposed to people who hold these beliefs? When the BC Administration welcomed Conservative columnist William F. B. O’Reilly to speak in front of the whole school this past Friday, they decided that yes, they should.

Mr. O’Reilly, the second speaker to participate in the school’s pre-election speaker series, was invited by the faculty and administration who thought it “essential that [we] include someone who does not identify as a Democrat, progressive, or liberal since most of the speakers we have at BC do identify that way,” said Upper School Director Jane Moore. She added that “some members of our community with more conservative viewpoints have reminded us that [Berkeley Carroll’s] culture does not tend to leave a lot of space for their opinions” and that “in an election series—in which there is always ‘another side’—having a speaker represent the non-majority opinion seemed especially important.” She went on to note that they selected someone who had “always been in the ‘never Trump’ camp” because “I and a number of others find many of Trump’s views both problematic and antithetical to the stated values of Berkeley Carroll.”

This controversial invitation was met with a variety of reactions including anger, excitement, approval, shock, and hurt. One student who wishes to remain anonymous was “surprised to hear that a conservative speaker was coming… and [was] intrigued to see how [it] would go.” Eugenie Haring ‘19 was worried that some would show up “prepared to fight” and without an “open mind,” a thought which was echoed by Logan McGraw ‘19 who predicted that Mr. O’Reilly would be “eaten alive.” Maija Fidelholtz ‘19 felt refreshed by Mr. O’Reilly’s arrival and stressed the importance of hearing “different viewpoints so that Berkeley Carroll students [are able to] break out of their bubble and expand their horizons,” as did Lisette McShane ‘19 who emphasized that the lack of ideas different from your own viewpoint does not “broaden your knowledge” but “limits your perspective on the world.”

However, not all students felt this way, including Camille Andrew ‘19, who thinks that visiting speakers “should conform to our values as a school and community.” Andrew feels that Mr. O’Reilly’s presence was “incredibly offensive and hurtful for the school.” Mosab Hamid ‘19 “strongly believe[s] that William F. B. O’Reilly should not have been invited to speak at Berkeley Carroll.” Hamid shares that although “Berkeley Carroll prides itself on being a safe space for everyone,” when Mr. O’Reilly came in to talk, “I did not feel safe. My fellow peers of color did not feel safe. We felt attacked.” Hamid declared, “I am upset, I am angry. I am disgusted at [O’Reilly’s] thinly veiled oppression that Berkeley Carroll decided to call diversity.” The intense distress and outrage felt by some members of the student body raises the question of who should be allowed to speak at Berkeley Carroll. Is it okay for our school to give a platform to potentially offensive speakers? How important is the representation of a diverse range of political ideas and what do we need to sacrifice in order to get it?

Many could argue that Berkeley Carroll lacks representation of non-progressive views and that the school exists in a liberal, utopian bubble. Discovering that a student or teacher is not a Democrat is often treated as a scandal and conservative ideas are quickly shut down on the rare occasion that they are shared in the first place. Defaced images of Donald Trump on Breakfast Club flyers as well as multiple anti-Trump references during Morning Meetings are common and unchallenged occurrences.

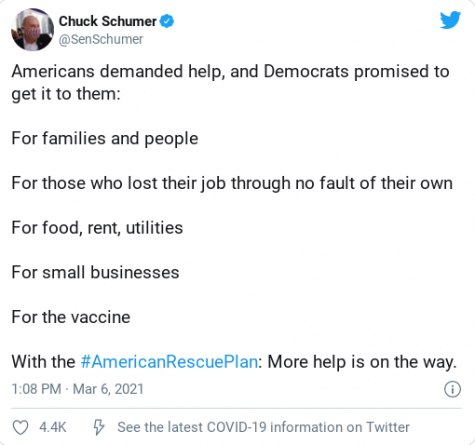

The University of Chicago made headlines this summer with their letter to the Class of 2020 that encouraged their student body to “speak, write, listen, challenge, and learn, without fear of censorship.” In order to make this happen, they stated that “they will not cancel invited speakers because their topic might prove controversial” and they will not “condone the creation of intellectual ‘safe spaces’ where individuals can retreat from ideas and perspectives at odds with their own.” In their letter, The University of Chicago promoted their “commitment to freedom of inquiry and expression” and stressed the value of free speech. However, free speech comes with a cost and not all schools agree with this now infamous letter.

According to Nina Burleigh, in an article for Newsweek, more than half of America’s colleges and universities now have restrictive speech codes in an effort to protect their students from potentially upsetting and offensive speakers. Safety is an empirical prerequisite to learning; when speakers who have the potential to trigger students and make them feel both uncomfortable and unsafe in their own schools are hosted, the quality of students’ education suffers. In addition, hate speech and free speech can easily and dangerously be confused. When this happens, the mental well being of students is put at risk and the civil rights of many can be violated. However, it is important to keep in mind that hate speech isn’t everything one disagrees with and that constraint of free speech is dangerous and harmful as well.

While Mr. O’Reilly is not a radical Republican, only a small minority of people at BC share his views. His presence sent waves through our community and invoked a strong and emotional response from many. It is generally understood in our community that diversity is imperative, but is there a way to expose ourselves to different ways of thinking in a safe way? Zachary Wood, a sophomore at Williams College led an on-campus lecture series called “Uncomfortable Learning,” driven by his desire to “challenge young progressives cloistered in a collegiate utopia.” Wood, an African American and self-described liberal who was raised in a poor D.C neighborhood, invited controversial and mostly right-wing speakers to his series before it was quelled by the administration. Wood maintains that “students need to hear provocateurs… in order to formulate their own thoughts and challenges” and that it is crucial that “we confront offensive views and afford college students the opportunity to learn how to engage constructively with people they vehemently disagree with.” This is all especially important this election season.

As a community, how do we expose ourselves to different ways of thinking in a safe way? Part of Berkeley Carroll’s Mission is to develop “critical, ethical, and global” thinkers and to allow students to find their “inner voices and begin to make sense of their place in the world.” If we don’t hear all sides of the story, are we effectively able to think for ourselves and figure out who we really are? In order to understand our complex world, “the confidence and ability to engage respectfully with others” is a critical skill. Wood asserts that “at a time like this, uncomfortable learning is vital.” How do we, as members of the Berkeley Carroll community, embrace discomfort and diversity safely as we all strive to be open-minded, tolerant, respectful, responsible, “critical, ethical, and global” citizens?