The Science Research Class Asks: iPads or Paper?

Apple has been spewing out iPads and iPhones to the public every year. More and more people are buying their products because they are useful and in style. More and more schools, like the Berkeley Carroll School, are buying iPads because they are efficient. Students can use apps such as iTUNESU, goodnotes, and google drive to organize their assignments, take notes, and share their work with teachers. Teachers can also use iTUNESU and iBooks to share their presentations, notes, homework assignments, and textbooks with students. Because iPads have many functions, they allow students to be prepared for every class. Not only do they seem efficient, but they also seem to complement the school’s curriculum.

The Junior Advanced Science Research and Design class brought this “complementation” into question. They did an experiment to see whether reading on the iPad or on paper would affect reading comprehension levels (their paper is posted below). During the process, students were separated into 4 groups: Background, Experimental, Data Analysis and Conclusions, and Overall Editing/Managing. Each group was responsible for communicating with others to get their task done, and writing their section in the final paper. Many students thought that collaboration with teachers and other members of the class was effective while performing the experiment and writing the paper. A person who wished to be anonymous remembered “Communication with teachers was great. We emailed them explaining our experiment and they were happy to set up a time and meet with us.” Kirsten Ebenezer (part of the Editing/Managing group) agreed, “Everyone was prompt when it came to altering their work. For instance, When we wanted to change some of the graphs and data, we asked Angela and Nadine [part of the Data Analysis and Conclusions group] to do so and they completed the task within a few days. People also realized that it was necessary for them to finish their work so that we could edit the paper and make it more concise.” When asked how the experiment could be improved, Aaron Goldin pensively stated, “I wish we could have tested more people so that we could get a significant result.” From interviews with students, it was noticeable that the class was able to perform the experiment and write the paper efficiently.

Although there was no significant conclusion, the experiment presented an important conclusion: There may not be a difference between reading on the iPad and on paper. This paper is being published in order to share this finding with the BC community. Papers such as these are crucial because they demonstrate the impact iPads and other devices have on the population, which should be considered in the progressing era of technology.

Comparing Reading Comprehension Accuracy on iPad versus Paper

By: Camille Johnson, Kirsten Ebenezer, Michelle Madlansacay, Emma Raible, Nadine Khoury, Angela Goldshteyn, Elias Contrubis, Max Wu, Gil Ferguson, Zoe Denckla, Thomas Shea, Jimmy Council, Aaron Goldin, Stephanie Aquino, Danielle Cheffo, Scott Rubin

Abstract

The Advanced Science Research and Design class conducted a group study to determine if reading on an iPad or reading on paper affects the reading comprehension of Berkeley Carroll students. This was tested on a class of 5th graders, 9th graders, and 12th graders. To do this study, a class was given a reading. Half of the class did that reading on an iPad, and half on paper. They were then given a multiple choice quiz. On another day, the classes followed the same steps, but the groups switched, and the group that first read on paper, now read on iPads, and vice versa. Though average quiz scores were better after reading on paper, it was concluded that there was no significant difference between the scores of students who read on the iPad and students who read on paper.

Background

Over time, technology has become an essential part of our lives. As technology advances, society must advance along with it. An issue that often comes up in the discussion of technology is how it may affect the education of young students. Many schools like Berkeley Carroll have begun to integrate technology into their curriculums, usually replacing the classic chalk boards and paperback books with Smartboards and tablets. The reason for such change, according to Berkeley Carroll’s Director of Technology Aidan Lucey, was to “reduce the use of paper” as well as make the students more “tech relevant.”

However more exposure to technology does not necessarily guarantee effective learning. The study of comparing reading on a tablet, to reading on a paperback book is essential because many people have different preferences. Identifying the majority opinion in this debate of “iPads vs. paper” will help schools determine the right time to integrate technology into the curriculum, and even if such an advancement will be effective.

In the reading world, there are those who prefer the classic paperback book and those who have become as productive reading on a tablet. For the readers with a preference of paperback books, the idea of haptic dissonance gives a better explanation of their views. The term haptic dissonance is used to describe the lack of a particular “feel” when reading an actual book (Gerlach, Jin and Buxmann, Peter). A large benefit of reading a classic paperback is that you may feel a better sense of ownership over the pages you hold (you have more of a physical lay of the land), which is not a feeling present while reading on an iPad. As mentioned in an article from Scientific American, “turning the pages of a paper book is like leaving one footprint after another on the trail—there’s a rhythm to it and a visible record of how far one has traveled.” (The Reading Brain in the Digital Age: The Science of Paper versus Screens) The tangible journey of reading entices such readers, although personal preference plays more of a role in this debate. Paperback readers may feel as though they can “navigate intellectually through physicality”, as stated by Berkeley Carroll Middle School director, Mr. James Shapiro. However iPad fanatics may find it easier and more convenient to read on the tablet. For some, the tablet helps because “if you tend to read quickly, you take chunks of words. Sometimes the screen on a tablet promotes reading faster,” according to the Head of School, Mr. Robert Vitalo. An iPad would also allow young readers to expand their knowledge of technology, making them more comfortable using modern equipment (which is a very useful life skill).

Experimental studies have been conducted in the past to compare reading on screens (tablet PC) with reading on paper. Particularly, in 2011 a study in Turkey had taken place, in which two groups of 5th graders (20 people) would read three passages on either a tablet or on paper. Afterwards, the students answered reading comprehension questions. With evaluating the study’s findings, the researchers mainly observed the students’ answers to the comprehension questions, and the speed at which they orally read the passages. We did not specifically observe reading speed in our study. The study in Turkey concluded that there was no significant difference between the two groups, in either comprehension or reading speed.

After the third year of the iPad program, 11th grade students from the Berkeley Carroll Science Research and Design Program have conducted their own study: comparing the reading on an iPad with reading on paper. Our study involved more subjects than the study in Turkey, so it led us to believe that our results may be more conclusive than theirs. This is an important topic to research because technology is especially advancing in modern society and educators are constantly looking for new ways to update their teaching.

Procedure

- Identify a 5th, 9th and 12th grade teacher who volunteers their class to participate in the experiment (n=16 for 5th grade; n=15 for 9th grade; n=14 for 12th grade).

- Choose 2 readings (excerpts from books, articles etc.) by meeting with each teacher to select an appropriate level of reading for each grade level.

- Create quizzes with teacher to assure they are an appropriate level for each of the two readings.

- Randomly split each class into two groups: one reading on iPads and the other reading on paper.

- Hand out paper reading and share iPad reading on iTunes U.

- Have students read the chosen article/excerpt.

- After participants finish reading, take away readings and close iPads.

- Distribute quizzes all on paper and have subjects fill out quizzes.

- Collect quizzes, grade them and record the data.

- Next available class time, switch the reading and switch up the groups so that the students who read on iPads now read on paper and vice versa and repeat the study.

Results

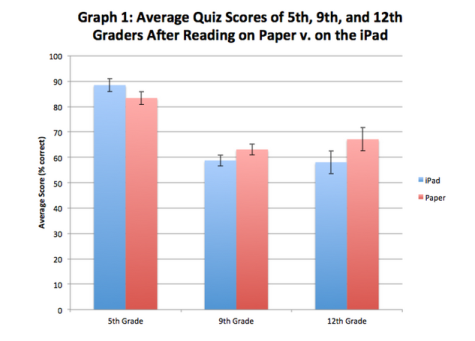

Graph 1 shows the average test scores for each grade when students took quizzes after reading an excerpt on the iPad or on paper. Independent, 2-tailed t-tests were conducted and they showed that all p-values were greater than 0.05 (p-value=0.48 for 5th graders; p-value=0.61 9th graders; p-value= 0.25 for 12th graders). Therefore, there is no significant evidence that students retained more information when reading on paper rather than the iPad.

Data Tables and Graphs

Table 1: Average Scores of 5th, 9th, and 12th Grade Students

| Average Scores of 5th Grade Students (%) | Average Scores of 9th Grade Students (%) | Average scores of 12th Grade Students (%) | |||||||

| iPad | Paper | Total Average | iPad | Paper | Total Average | iPad | Paper | Total Average | |

| Quiz 1 | 87.5 | 100 | 93.8 | 43.8 | 57.1 | 50 | 60 | 74.4 | 67.2 |

| Quiz 2 | 89.5 | 66.7 | 78.1 | 73.8 | 69 | 71.4 | 57.3 | 61 | 59.4 |

| Total Average | 88.5 | 83.3 | 85.9 | 59.1 | 63.6 | 61.3 | 58.8 | 67.2 | 63.3 |

This shows the average quiz scores for 5th, 9th, and 12th grade students who read on the iPad and on paper and the total average score for each quiz. For 5th grade, students who read on paper did better than students who read on the iPad during the first quiz and students who read on the iPad did better than students who read on paper during the second quiz. The total average decreased from the first quiz to the second quiz. For 9th grade, students who read on paper did better than students who read on the iPad during the first quiz and students who read on the iPad did better than students who read on paper during the second quiz. The total average increased from the first quiz to second quiz. For 12th grade, students who read on paper did better than students who read on the iPad for the first and second quiz. The total average decreased from the first quiz to the second quiz.

Graph 1 shows the average quiz scores for 5th, 9th, and 12th grade students who read on the ipad and on paper.

Analysis and Discussion

There were two quizzes that showed higher quiz scores for students who read on the iPad rather than on paper. First, 5th graders obtained a total score of 89.5% for one of the two quizzes they took after reading on their iPads compared to a total score of 66.7% after reading on paper (Table 1). Second, 9th graders obtained a total score of 73.8% for a quiz they took after reading on their iPads compared to a total score of 69% after reading on paper (Table 2). This might be due to the skill level of individual students. During Quiz 1, half of the class read on the iPad and the other half read on paper. During Quiz 2, the same half that read on the iPad switched to paper and vice versa. Thus, ninth and fifth graders who read on paper during Quiz 1 might have been collectively better at reading comprehension than the other half, which allowed them to earn higher scores regardless of whether they read on the iPad or on paper. In future it might be advisable to select students of similar skill levels instead of randomly assigning them to groups.

Another factor that could have affected the results was the difficulty level of the quizzes. For instance, 9th graders’ total average scores were higher on the second quiz than that of the first quiz. Table 2 shows that a total average score of 50% was obtained for the first quiz and 71.4% was obtained for the second quiz. Because average scores increased for students that read on the iPad and on paper, difficulty levels of the quizzes did not affect these results. The opposite was seen in Table 3, where quiz scores from Quiz 1 were approximately 8% lower than those of Quiz 2. These two cases depict the random error involved in the experiment. One quiz may have yielded lower or higher average scores for multiple reasons: a quiz may have taken place on a stressful day for students, students may not have read the assigned reading closely (e.g. some may have just skimmed and others may not have read it at all), or one quiz may have been harder than the other.

Conclusion

As technology becomes extremely prevalent in daily life, it is important to see if there are any distinguishing or rather ‘more effective’ ways in which students can improve their educational experience and at the same time adapt themselves to become more “tech relevant”. For this reason, the group study experiment was conducted to discover if a certain medium of print– electronic or paper has an effect on reading comprehension. The results show that there was no significant difference that explicitly showed that there is one preferred method. The p-values that were gathered after an independent, 2-tailed t-test was conducted was 0.48 for 5th graders, 0.61 for 9th graders, and 0.25 for 12th graders. If the sample size had been bigger the results could have been more conclusive

This study could be improved by increasing sample size or selecting for students based on their achievement rather than by grouping them randomly. Ultimately, the results showed that for Berkeley Carroll students, there is no significant difference when one is using either an iPad or paper to test reading comprehension.

Works Cited for Literature Review:

Dillon, Andrew. “Reading from Paper versus Screens: A Critical Review of the Empirical

Literature.” . N.p., 1992. Web. 20 Nov. 2014.

<https://www.ischool.utexas.edu/~adillon/Journals/Reading.htm>.

Dundar, Hakan, and Murat Akcayir. “Tablet vs. Paper: The Effect on Learners’ Reading

Performance.” International Electronic Journal of Elementary Education (2012): n. pag. Web.

Gerlach, Jin and Buxmann, Peter, “INVESTIGATING THE ACCEPTANCE OF ELECTRONIC BOOKS – THE IMPACT OF HAPTIC DISSONANCE ON INNOVATION ADOPTION” (2011).ECIS 2011 Proceedings. Paper 141.

http://aisel.aisnet.org/ecis2011/141

Jabr, Ferris. “The Reading Brain in the Digital Age: The Science of Paper versus Screens.” Scientific American Global RSS. N.p., 11 Apr. 2013. Web. 20 Nov. 2014. <http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/reading-paper-screens/>.

Personal Communication: Aidan Lucey, Robert Vitalo and James Shapiro (Fall 2014)